AIPT Section 3.2: Solving Poker – Toy Poker Games

Solving Poker - Toy Poker Games

We will take a look at solving a very simple toy poker game called Kuhn Poker using multiple techniques that are increasingly efficient. Starting with Section 4, we will go into the Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR) algorithm that has been the standard in solving imperfect information games since 2007.

Kuhn Poker

Kuhn Poker is the most basic poker game with interesting strategic implications. We mentioned it in the Poker Background section and will summarize the rules here as well.

The game in its standard form is played with 3 cards {A, K, Q} and 2 players. Each player starts with \$2 and places an ante (i.e., forced bet before the hand) of \$1. And therefore has \$1 left to bet with. Each player is then dealt 1 card and 1 round of betting ensues.

The rules in bullet form:

- 2 players

- 3 card deck {A, K, Q}

- Each starts the hand with $2

- Each antes (i.e., makes forced bet of) $1 at the start of the hand

- Each player is dealt 1 card

- Each has $1 remaining for betting

- There is 1 betting round and 1 bet size of $1

- The highest card is the best (i.e., A $>$ K $>$ Q)

Action starts with P1, who can Bet $1 or Check

- If P1 bets, P2 can either Call or Fold

- If P1 checks, P2 can either Bet or Check

- If P2 bets after P1 checks, P1 can then Call or Fold

These outcomes are possible:

- If a player folds to a bet, the other player wins the pot of $2 (profit of \$1)

- If both players check, the highest card player wins the pot of $2 (profit of \$1)

- If there is a bet and call, the highest card player wins the pot of $4 (profit of \$2)

The following are all of the possible full sequences.

The “History full” shows the exact betting history with “k” for check, “b” for bet, “c” for call, “f” for fold.

The “History short” uses a condensed format that uses only “b” for betting/calling and “p” (pass) for checking/folding, meaning that “b” is used when putting $1 into the pot and “p” when putting no money into the pot. We reference this shorthand format since we’ll use it when putting the game into code.

| P1 | P2 | P1 | Pot size | Result | History full | History short |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check | Check | – | $2 | High card wins $1 | kk | pp |

| Check | Bet $1 | Call $1 | $4 | High card wins $2 | kbc | pbb |

| Check | Bet $1 | Fold | $2 | P2 wins $1 | kbf | pbp |

| Bet $1 | Call $1 | – | $4 | High card wins $2 | bc | bb |

| Bet $1 | Fold | – | $2 | P1 wins $1 | bf | bp |

Solving Kuhn Poker

We’re going to solve for the GTO solution to this game using 3 methods, an analytical solution, a normal form solution, and then a more efficient extensive form solution. We will then briefly mention game trees and the CFR counterfactual regret algorithm, that will be detailed more in section 4.1.

What’s the point of solving such a simple game? We can learn some important poker principles even from this game, although they are most useful for beginner players. We can also see the limitations of these earlier solving methods and therefore why new methods were needed to solve games of even moderate size.

Analytical Solution

There are 4 decision points in this game: P1’s opening action, P2 after P1 bets, P2 after P1 checks, and P1 after checking and P2 betting.

Defining the variables

P1 initial action

Let’s first look at P1’s opening action. P1 should never bet the K card here because if he bets the K, P2 with Q will always fold (since the lowest card can never win) and P2 with A will always call (since the best card will always win). By checking the K always, P1 can try to induce a bluff from P2 when P2 has the Q and may be able to fold to a bet when P2 has the A.

Therefore we assign P1’s strategy:

- Bet Q: \(x\)

- Bet K: \(0\)

- Bet A: \(y\)

P2 after P1 bet

After P1 bets, P2 should always call with the A and always fold the Q as explained above.

Therefore we assign P2’s strategy after P1 bet:

- Call Q: \(0\)

- Call K: \(a\)

- Call A: \(1\)

P2 after P1 check

After P1 checks, P2 should never bet with the K for the same reason as P1 should never initially bet with the K.

P2 should always bet with the A because it is the best hand and there is no bluff to induce by checking (the hand would simply end and P2 would win, but not have a chance to win more by betting).

Therefore we assign P2’s strategy after P1 check:

- Bet Q: \(b\)

- Bet K: \(0\)

- Bet A: \(1\)

P1 after P1 check and P2 bet

This case is similar to P2’s actions after P1’s bet. P1 can never call here with the worst hand (Q) and must always call with the best hand (A).

Therefore we assign P1’s strategy after P1 check and P2 bet:

- Call Q: \(0\)

- Call K: \(z\)

- Call A: \(1\)

So we now have 5 different variables \(x, y, z\) for P1 and \(a, b\) for P2 to represent the unknown probabilities.

Solving for the variables

The Indifference Principle

When we solve for the analytical game theory optimal strategy, we want to make the opponent indifferent. This means that the opponent cannot exploit our strategy. If we deviated from this equilibrium then since poker is a 2-player zero-sum game, our opponent’s EV could increase at the expense of our own EV.

Solving for \(x\) and \(y\)

For P1 opening the action, \(x\) is his probability of betting with Q (bluffing) and \(y\) is his probability of betting with A (value betting). We want to make P2 indifferent between calling and folding with the K (since again, Q is always a fold and A is always a call for P2).

When P2 has K, P1 has \(\frac{1}{2}\) of having a Q and A each.

P2’s EV of folding with a K to a bet is \(0\). (Note that we are defining EV from the current decision point, meaning that money already put into the pot is sunk and not factored in.)

P2’s EV of calling with a K to a bet

\[= 3 * \text{P(P1 has Q and bets with Q)} + \\(-1) * \text{P(P1 has A and bets with A)}\] \[= (3) * \frac{1}{2} * x + (-1) * \frac{1}{2} * y\]Setting the calling and folding EVs equal (because of the indifference principle), we have:

\[0 = (3) * \frac{1}{2} * x + (-1) * \frac{1}{2} * y\] \[y = 3 * x\]That is, P1 should bet the A 3 times more than bluffing with the Q. This result is parametrized, meaning that there isn’t a fixed number solution, but rather a ratio of how often P1 should value-bet compared to bluff. For example, if P1 bluffs with the Q 10% of the time, he should value bet with the A 30% of the time.

Solving for \(a\)

\(a\) is how often P2 should call with a K facing a bet from P1.

P2 should call \(a\) to make P1 indifferent to bluffing (i.e., betting or checking) with card Q.

If P1 checks with card Q, P1 will always fold afterwards if P2 bets (because it is the worst card and can never win), so P1’s EV is 0.

\[\text{EV P1 check with Q} = 0\]If P1 bets with card Q,

\[\text{EV P1 bet with Q} = (-1) * \text{P2 has A and always calls/wins} + \\(-1) * \text{P2 has K and calls/wins} + 2 * \text{P2 has K and folds}\] \[= \frac{1}{2} * (-1) + \frac{1}{2} * (a) * (-1) + \frac{1}{2} * (1 - a) * (2)\] \[= -\frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2} * a + (1 - a)\] \[= \frac{1}{2} - \frac{3}{2} * a\]Setting the probabilities of betting with Q and checking with Q equal, we have:

\[0 = \frac{1}{2} - \frac{3}{2} * a\] \[\frac{3}{2} * a = \frac{1}{2}\] \[a = \frac{1}{3}\]Therefore P2 should call \(\frac{1}{3}\) with a K when facing a bet from P1.

Solving for \(b\)

Now to solve for \(b\), how often P2 should bet with a Q after P1 checks. The indifference for P1 is only relevant when he has a K, since if he has a Q or A, he will always fold or call, respectively.

If P1 checks a K and then folds, then:

\[\text{EV P1 check with K and then fold to bet} = 0\]If P1 checks and calls, we have:

\[\text{EV P1 check with K and then call a bet} = (-1) * \text{P(P2 has A and always bets) + (3) * P(P2 has Q and bets)\] \[= \frac{1}{2} * (-1) + \frac{1}{2} * b * (3)\]Setting these probabilities equal, we have:

\[0 = \frac{1}{2} * (-1) + \frac{1}{2} * b * (3)\] \[\frac{1}{2} = \frac{1}{2} * b * (3)\] \[3 * b = 1\] \[b = \frac{1}{3}\]Therefore P2 should bet \(\frac{1}{3}\) with a Q after P1 checks.

Solving for \(z\)

The final case is when P1 checks a K, P2 bets, and P1 must decide how frequently to call so that P2 is indifferent to checking vs. betting (bluffing) with a Q.

(Note that \| denotes “given that” and we use the conditional probability formula of \(\text{P(A\\|B)} = \frac{P(A \cup B)}{P(B)}\) where \(\cup\) denotes the intersection of the sets, so in this case is where \(A\) and \(B\) intersect – by intersect we just mean that they are both true at the same time, like the middle part of a Venn diagram)

We start with finding the probability that P1 has an A given that P1 has checked and P2 has a Q, meaning that P1 has an A or K.

\[\text{P(P1 has A | P1 checks A or K)} = \frac{\text{P(P1 has A and checks)}}{\text{P(P1 checks A or K)}}\]We simplify the numerator to P1 having A and checking because there is no intersection between checking a K and having an A.

\[= \frac{(1-y) * \frac{1}{2}}{(1-y) * \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}}\] \[= \frac{1-y}{2-y}\] \[\text{P(P1 has K | P1 checks A or K)} = 1 - \text{P(P1 has A | P1 checks A or K)}\] \[= 1 - \frac{1-y}{2-y}\] \[= \frac{2-y}{2-y} - \frac{1-y}{2-y}\] \[= \frac{1}{2-y}\]If P2 checks his Q, his EV \(= 0\).

If P2 bets (bluffs) with his Q, his EV is:

\[-1 * \text{P(P1 check A then call A)} - 1 * \text{P(P1 check K then call K)} + 2 * \text{P(P1 check K then fold K)}\] \[= -1 * \frac{1-y}{2-y} + -1 * z * \frac{1}{2-y} + 2 * (1-z) * \frac{1}{2-ya}\]Setting these equal:

\[0 = -1 * \frac{1-y}{2-y} + -1 * z * \frac{1}{2-y} + 2 * (1-z) * \frac{1}{2-y}\] \[0 = -1 * \frac{1-y}{2-y} + -1 * z * \frac{1}{2-y} + 2 * (1-z) * \frac{1}{2-y}\] \[0 = -\frac{1-y}{2-y} - z * \frac{3}{2-y} + \frac{2}{2-y}\] \[z * \frac{3}{2-y} = \frac{2}{2-y} - \frac{1-y}{2-y}\] \[z = \frac{2}{3} - \frac{1-y}{3}\] \[z = \frac{y+1}{3}\]So P1 should call with a K relative to the proportion of betting an A. This means if betting A 50% of the time (\(y=0.5\)), we would have \(z = \frac{1.5}{3} = 0.5\) as well.

Solution summary

We now have the following result:

P1 initial actions:

Bet Q: \(x = \frac{y}{3}\)

Bet A: \(y = 3*x\)

P2 after P1 bet:

Call K: \(a = \frac{1}{3}\)

P2 after P1 check:

Bet Q: \(b = \frac{1}{3}\)

P1 after P1 check and P2 bet:

Call K: \(z = \frac{y+1}{3}\)

P2 has fixed actions, but P1’s are dependent on the \(y\) parameter.

Finding the game value

We can look at the expected value of every possible deal-out to evaluate the value for \(y\). We format these EV calculations as \(\text{P1 action} * \text{P2 action} * \text{P1 action if applicable} * \text{EV}\), all from the perspective of P1.

Case 1: P1 A, P2 K

- Bet fold:

- Bet call:

- Check check:

Total = \(\frac{y}{3} + 2\)

Case 2: P1 A, P2 Q

- Bet fold:

- Check bet call:

- Check check:

Total = \(2 * y + (1 - y) + \frac{4}{3} * (1-y) = \frac{1}{3} * (7 - y)\)

Case 3: P1 K, P2 A

- Check bet call:

- Check bet fold:

Total = \(-\frac{y+1}{3}\)

Case 4: P1 K, P2 Q

- Check check:

- Check bet call:

- Check bet fold:

Total = \(\frac{4}{3} + \frac{y+1}{3} = \frac{y+5}{3}\)

Case 5: P1 Q, P2 A

- Bet call:

- Check bet fold:

Total = \(\frac{-y}{3}\)

Case 6: P1 Q, P2 K

- Bet call:

- Bet fold:

- Check check:

Total = \(-\frac{y}{9} + \frac{4*y}{9} = \frac{y}{3}\)

Summing up the cases Since each case is equally likely based on the initial deal, we can multiply each by \(\frac{1}{6}\) and then sum them to find the EV of the game. Summing up all cases, we have:

Overall total = \(\frac{1}{6} * [\frac{y}{3} + 2 + \frac{1}{3} * (7 - y) + -\frac{y+1}{3} + \frac{y+5}{3} + \frac{-y}{3} + \frac{y}{3}] = \frac{17}{18}\)

Main takeaways

What does this number \(\frac{17}{18}\) mean? It says that the expectation of the game from the perspective of Player 1 is \(\frac{17}{18}\). Since this is \(<1\), we see that the expected gain from playing the game of Player 1 is \(1 - \frac{17}{18} = -0.05555\). This is because for each $1 put into the game, Player 1 is expected to get back \(\frac{17}{18}\) and so is expected to lose. Therefore the value of the game for Player 2 is \(+0.05555\).

Every time that these players play a hand against each other (assuming they play the equilibrium strategies), that will be the outcome on average – meaning P1 will lose \(\$5.56\) on average per 100 hands and P2 will gain that amount. However, since in practice players rotate between being Player 1 and Player 2, both players will be guaranteed to breakeven if playing the Nash equilibrium.

This indicates the advantage of acting last in poker – seeing what the opponent has done first gives an information advantage. In this game, the players would rotate who acts first for each hand, but the principle of playing more hands with the positional advantage is very important in real poker games and is why good players are much looser in later positions at the table.

The expected value is not at all dependent on the \(y\) variable which defines how often Player 1 bets his A hands. If we assumed that the pot was not a fixed size of \$2 to start the hand, then it would be optimal for P1 to either always bet or always check the A (the math above would change and the result would depend on \(y\)), but we’ll stick with the simple case of the pot always starting at \$2 from the antes.

From a poker strategy perspective, the main takeaway is that we can essentially split our hands into:

- Strong hands

- Mid-strength hands

- Weak hands

Mid-strength hands can win, but don’t want to build the pot. Strong hands try to generally make the pot large with value bets (though can also be used deceptively). Weak hands want to either give up or be used as bluffs. There is a major polarization effect where strong and weak hands have similarities and mid-strength hands are played passively.

Note that this mathematically optimal solution automatically uses bluffs. Bluffs are not -EV bets that are used as “bad plays” to get more credit for value bets later, they are part of an overall optimal strategy.

We also see that a major component of poker strategy is “balancing” bluffs. We see that P1 value bets 3 times more than she bluffs. In a real poker setting, you might have a similar strategy, but will have many possible bluff hands in your range to choose from, which means that they can be strategically selected to match the ratio, for example by bluffing with hands that make it less likely that your opponent is strong, while giving up with other weak hands.

Finally, there are many cases where the probabilities are 0 or 1. Often, these represent obvious actions where the player is definitely winning or losing so has no incentive to do anything else. For example, the “Jack, bet (after bet)” (i.e. calling a bet with the worst hand) would not make sense because he can’t be winning and the “King, pass (after pass)” (i.e. not betting with the best hand when there’s no action to go) is the reverse, because he must be winning.

One interesting case of 0 probability is “Queen, bet” because if the first acting player bets with a Queen, he will certainly be called and lose to a King and will certainly force the inferior Jack to fold, therefore this action should never be taken. This illustrates the poker concept of not betting middling hands, since there is a high probability that only better hands will call and you will force worse hands to fold.

Kuhn Poker in Normal Form

Analytically solving all but the smallest games is not very feasible – a faster way to compute the strategy for this game is putting it into normal form.

Information sets

There are 6 possible deals in Kuhn Poker: AK, AQ, KQ, KA, QK, QA.

Each player has 2 decision points in the game. Player 1 has the initial action and the action after the sequence of P1 checks –> P2 bets. Player 2 has the second action after Player 1 bets or Player 1 checks.

Therefore each player has 12 possible acting states. For player 1 these are (where the first card belongs to Player 1 and the second card belongs to Player 2):

- AK acting first

- AQ acting first

- KQ acting first

- KA acting first

- QK acting first

- QA acting first

- AK check, P2 bets, P1 action

- AQ check, P2 bets, P1 action

- KQ check, P2 bets, P1 action

- KA check, P2 bets, P1 action

- QK check, P2 bets, P1 action

- QA check, P2 bets, P1 action

However, the state of the game (or world of the game) is not actually known to the players! Each player has 2 decision points that are equivalent from their point of view, even though the true game state is different. For player 1 these are:

- A acting first (combines AK and AQ)

- K acting first (combines KQ and KA)

- Q acting first (combines QK and QA)

- A check, P2 bets, P1 action (combines AK and AQ)

- K check, P2 bets, P1 action (combines KQ and KA)

- Q check, P2 bets, P1 action (combines QK and QA)

From Player 1’s perspective, she only knows her own private card and can only make decisions based on knowledge of this card.

For example, if Player 1 is dealt a K and Player 2 dealt a Q or P1 dealt K and P2 dealt A, P1 is facing the decision of having a K and starting the betting not knowing what the opponent has.

Likewise if Player 2 is dealt a K and is facing a bet, he must make the same action regardless of what the opponent has because from his perspective he only knows his own card and the action history.

We define an information set as the set of information used to make decisions at a particular point in the game. In Kuhn Poker, it is equivalent to the card of the acting player and the history of actions up to that point.

When writing game history sequences, we use “k” to define check, “b” for bet”, “f” for fold, and “c” for call. So for Player 1 acting first with a K, the information set is “K”. For Player 2 acting second with an A and facing a bet, the information set is “Ab”. For Player 2 acting second with a A and facing a check, the information set is “Ak”. For Player 1 with a K checking and facing a bet from Player 2, the information set is “Kkb”.

The shorthand version in the case of Kuhn Poker is to combine “k” and “f” into “p” for pass and to combine “b” and “c” into “b” for bet. Pass indicates putting no money into the pot and bet indicates putting $1 into the pot.

Writing Kuhn Poker in Normal Form

Now that we have defined information sets, we see that each player in fact has 2 information sets per card that he can be dealt, which is a total of 6 information sets per player since each can be dealt a card in {Q, K, A}. (If the game was played with a larger deck size, then we would have \(\text{N} * 2\) information sets, where N is the deck size.)

Each information set has two actions possible, which are essentially “do not put money in the pot” (check when acting first/facing a check or fold when facing a bet – we call this pass) and “put in $1” (bet when acting first or call when facing a bet – we call this bet).

The result is that each player has \(2^6 = 64\) total combinations of pure strategies. Think of this as each player having a switch between pass/bet for each of the 6 information sets that can be on or off and deciding all of these in advance.

Here are a few examples of the 64 strategies for Player 1 (randomly selected):

- A - bet, Apb - bet, K - bet, Kpb - bet, Q - bet, Qpb - bet

- A - bet, Apb - bet, K - bet, Kpb - bet, Q - bet, Qpb - pass

- A - bet, Apb - bet, K - pass, Kpb - bet, Q - bet, Qpb - bet

- A - bet, Apb - pass, K - bet, Kpb - pass, Q - bet, Qpb - bet

- A - bet, Apb - pass, K - bet, Kpb - bet, Q - bet, Qpb - bet

- A - pass, Apb - bet, K - bet, Kpb - bet, Q - pass, Qpb - bet

We can create a \(64 \text{x} 64\) payoff matrix with every possible strategy for each player on each axis and the payoffs inside.

| P1/P2 | P2 Strat 1 | P2 Strat 2 | … | P2 Strat 64 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 Strat 1 | EV(1,1) | EV(1,2) | … | EV(1,64) |

| P1 Strat 2 | EV(2,1) | EV(2,2) | … | EV(2,64) |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| P1 Strat 64 | EV(64,1) | EV(64,2) | … | EV(64,64) |

This matrix has 4096 entries and would be difficult to use for something like iterated elimination of dominated strategies. We turn to linear programming to find a solution.

Solving with Linear Programming

The general way to solve a game matrix of this size is with linear programming, which is essentially a way to optimize a linear objective, which we’ll define below. This kind of setup could be used in a problem like minimizing the cost of food while still meeting objectives like a minimum number of calories and maximum number of carbohydrates and sugar.

We can define Player 1’s strategy as \(x\), which is a vector of size 64 corresponding to the probability of playing each strategy. We do the same for Player 2 as \(y\).

We define the payoff matrix as \(A\) with the payoffs written with respect to Player 1.

\[A = \quad \begin{bmatrix} EV(1,2) & EV(1,2) & ... & EV(1,64) & \\ EV(2,1) & EV(2,2) & ... & EV(2,64) & \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & \\ EV(64,1) & EV(64,2) & ... & EV(64,64) & \\ \end{bmatrix}\]We can use payoff matrix \(B\) for payoffs written with respect to Player 2 – in zero-sum games like poker, \(A = -B\), so it’s easiest to just use \(A\).

We can also define a constraint matrix for each player:

Let P1’s constraint matrix = \(E\) such that \(Ex = e\)

Let P2’s constraint matrix = \(F\) such that \(Fy = f\)

The only constraint we have at this time is that the sum of the strategies is 1 since they are a probability distribution (all probability distributions must add up to 1, for example the probabilities of getting heads (0.5) and tails (0.5) sum to 1), so \(E\) and \(F\) will just be vectors of 1’s and \(e\) and \(f\) will \(= 1\). In effect, this is just saying that each player has 64 strategies and should play each of those some % of the time (some will be 0) and these %s have to add up to 1 since this is a probability distribution and probabilities always add up to 1.

In the case of Kuhn Poker, for step 1 we look at a best response for Player 2 (strategy y) to a fixed Player 1 (strategy x) and have the following. Best response means best possible strategy for Player 2 given Player 1’s fixed strategy.

\[\max_{y} (x^TB)y\] \[\text{Such that: } Fy = f, y \geq 0\]We are looking for the strategy parameters \(y\) that maximize the payoffs for Player 2. \(x^TB\) is the transpose of \(x\) multiplied by \(B\), so the strategy of Player 1 multiplied by the payoffs to Player 2. Player 2 then can choose \(y\) to maximize his payoffs.

We substitute \(-A\) for \(B\) so we only have to work with the \(A\) matrix.

\[= \max_{y} (x^T(-A))y\]We can substitute \(-A\) with \(A\) and change our optimization to minimizing instead of maximizing.

\[= \min_{y} (x^T(A))y\] \[\text{Such that: } Fy = f, y \geq 0\]In words, this is the expected value of the game from Player 2’s perspective because the \(x\) and \(y\) matrices represent the probability of ending in each state of the payoff matrix and the \(B == -A\) value represents the payoff matrix itself. So Player 2 is trying to find a strategy \(y\) that maximizes the payoff of the game from his perspective against a fixed \(x\) player 1 strategy.

For step 2, we look at a best response for Player 1 (strategy x) to a fixed Player 2 (strategy y) and have:

\[\max_{x} x^T(Ay)\] \[\text{Such that: } x^TE^T = e^T, x \geq 0\]Note that now Player 1 is trying to maximize this equation and Player 2 is trying to minimize this same thing.

For step 3, we can combine the above 2 parts and now allow for \(x\) and \(y\) to no longer be fixed, which leads to the below minimax equation. In 2-player zero-sum games, the minimax solution is the same as the Nash equilibrium solution. We call this minimax because each player minimizes the maximum payoff possible for the other – since the game is zero-sum, they also minimize their own maximum loss (maximizing their minimum payoff). This is also why the Nash equilibrium strategy in poker can be thought of as a “defensive” strategy, since by minimizing the maximum loss, we aren’t trying to maximally exploit.

\[\min_{y} \max_{x} [x^TAy]\] \[\text{Such that: } x^TE^T = e^T, x \geq 0, Fy = f, y \geq 0\]We can solve this with linear programming, but this would involve a huge payoff matrix \(A\) and length 64 strategy vectors for each player. There is a much more efficient way!

Solving by Simplifying the Matrix

Kuhn Poker is the most basic poker game possible and requires solving a \(64 \text{x} 64\) matrix. While this is feasible, any reasonably sized poker game would blow up the matrix size.

We can improve on this form by considering the structure of the game tree. Rather than just saying that the constraints on the \(x\) and \(y\) matrices are that they must sum to 1 as we did above, we can redefine these conditions according to the structure of the game tree.

Simplified Matrices for Player 1 with Behavioral Strategies

Previously we defined \(E = F = \text{Vectors of } 1\), which is the most basic constraint that all probabilities have to sum to 1.

However, we know that some strategic decisions can only be made after certain other decisions have already been made. For example, Player 2’s actions after a Player 1 bet can only be made after Player 1 has first bet!

Now we can redefine the \(E\) constraint as follows for Player 1:

| Infoset/Strategies | 0 | A_b | A_p | A_pb | A_pp | K_b | K_p | K_pb | K_pp | Q_b | Q_p | Q_pb | Q_pp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| A | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ap | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| K | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Kp | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Q | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Qp | -1 | 1 | 1 |

We see that \(E\) is a \(7 \text{x} 13\) matrix, representing the root of the game and the 6 information sets vertically and the root of the game and the 12 possible strategies horizontally. The difference now is that we are using behavioral strategies instead of mixed strategies. Mixed strategies meant specifying a probability of how often to play each of 64 possible pure strategies. Behavioral strategies assign probability distributions over strategies at each information set. Kuhn’s Theorem (the same Kuhn) states that in a game where players may remember all of their previous moves/states of the game available to them, for every mixed strategy there is a behavioral strategy that has an equivalent payoff (i.e. the strategies are equivalent).

Within the matrix, the [0,0] entry is a dummy and filled with a 1. Each row has a single -1, which indicates the strategy (or root) that must precede the infoset. For example, the A has a -1 entry at the root (0) and 1 entries for A_b and A_p since the A must precede those strategies. The \(1\) entries represent strategies that exist from a certain infoset. In matrix form we have \(E\) as below:

\[E = \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]\(x\) is a \(13 \text{x} 1\) matrix of probabilities to play each strategy.

\[x = \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ A_b \\ A_p \\ A_{pb} \\ A_{pp} \\ K_b \\ K_p \\ K_{pb} \\ K_{pp} \\ Q_b \\ Q_p \\ Q_{pb} \\ Q_{pp} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]We have finally that \(e\) is a \(7 \text{x} 1\) fixed matrix.

\[e = \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]So we have overall:

\[\quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ A_b \\ A_p \\ A_{pb} \\ A_{pp} \\ K_b \\ K_p \\ K_{pb} \\ K_{pp} \\ Q_b \\ Q_p \\ Q_{pb} \\ Q_{pp} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]What do the matrices mean?

To understand how the matrix multiplication works and why it makes sense, let’s look at each of the 7 multiplications (i.e., each row of \(E\) multiplied by the column vector of \(x\) \(=\) the corresponding row in the \(e\) column vector.

Row 1

We have \(1 \text{x} 1\) = 1. This is a “dummy”.

Row 2

\(-1 + A_b + A_p = 0\) \(A_b + A_p = 1\)

This is the simple constraint that the probability between the initial actions in the game when dealt an A must sum to 1.

Row 3 \(-A_p + A_{pb} + A_{pp} = 1\) \(A_{pb} + A_{pp} = A_p\)

The probabilities of Player 1 taking a bet or pass option with an A after initially passing must sum up to the probability of that initial pass \(A_p\).

The following are just repeats of Rows 2 and 3 with the other cards.

Row 4

\[-1 + K_b + K_p = 0\] \[K_b + K_p = 1\]The probabilities of Player 1’s initial actions with a K must sum to 1.

Row 5

\[-K_p + K_{pb} + K_{pp} = 1\] \[K_{pb} + K_{pp} = K_p\]The probabilities of Player 1 taking a bet or pass option with a K after initially passing must sum up to the probability of that initial pass \(K_p\).

Row 6

\[-1 + Q_b + Q_p = 0\] \[Q_b + Q_p = 1\]The probabilities of Player 1’s initial actions with a Q must sum to 1.

Row 7

\[-Q_p + Q_{pb} + Q_{pp} = 1\] \[Q_{pb} + Q_{pp} = Q_p\]The probabilities of Player 1 taking a bet or pass option with a Q after initially passing must sum up to the probability of that initial pass \(Q_p\).

Simplified Matrices for Player 2

And \(F\) works similarly for Player 2:

| Infoset/Strategies | 0 | A_b(ab) | A_p(ab) | A_b(ap) | A_p(ap) | K_b(ab) | K_p(ab) | K_b(ap) | K_p(ap) | Q_b(ab) | Q_p(ab) | Q_b(ap) | Q_p(ap) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Ab | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ap | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Kb | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Kp | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Qb | -1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Qp | -1 | 1 | 1 |

From the equivalent analysis as we did above with \(Fx = f\), we will see that each pair of 1’s in the \(F\) matrix will sum to \(1\) since they are the 2 options at the information set node.

Simplified Payoff Matrix

Now instead of the \(64 \text{x} 64\) matrix we made before, we can represent the payoff matrix as only \(6 \text{x} 2 \text{ x } 6\text{x}2 = 12 \text{x} 12\). (It’s actually \(13 \text{x} 13\) because we use a dummy row and column.) These payoffs are the actual results of the game when these strategies are played from the perspective of Player 1, where the results are in {-2, -1, 1, 2}.

| P1/P2 | 0 | A_b(ab) | A_p(ab) | A_b(ap) | A_p(ap) | K_b(ab) | K_p(ab) | K_b(ap) | K_p(ap) | Q_b(ab) | Q_p(ab) | Q_b(ap) | Q_p(ap) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | |||||||||||||

| A_b | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| A_p | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| A_pb | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| A_pp | -1 | -1 | |||||||||||

| K_b | -2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| K_p | -1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| K_pb | -2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| K_pp | -1 | -1 | |||||||||||

| Q_b | -2 | 1 | -2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Q_p | -1 | -1 | |||||||||||

| Q_pb | -2 | -2 | |||||||||||

| Q_pp | -1 | -1 |

And written in matrix form:

\[A = \quad \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & -2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]We could even further reduce this by eliminating dominated strategies:

| P1/P2 | 0 | A_b(ab) | A_b(ap) | A_p(ap) | K_b(ab) | K_p(ab) | K_b(ap) | K_p(ap) | Q_b(ab) | Q_p(ab) | Q_b(ap) | Q_p(ap) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||||||||||||

| A_b | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| A_p | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| A_pb | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||

| K_p | -1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| K_pb | -2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| K_pp | -1 | -1 | ||||||||||

| Q_b | 1 | -2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Q_p | -1 | -1 | ||||||||||

| Q_pp | -1 | -1 |

For simplicity, let’s stick with the original \(A\) payoff matrix and see how we can solve for the strategies and value of the game.

Simplified Linear Program

Our linear program is now updated as follows. It is the same general form as before, but now our \(E\) and \(F\) matrices have constraints based on the game tree and the payoff matrix \(A\) is smaller, evaluating when player strategies coincide and result in payoffs, rather than looking at every possible set of pure strategic options as we did before:

\[\min_{y} \max_{x} [x^TAy]\] \[\text{Such that: } x^TE^T = e^T, x \geq 0, Fy = f, y \geq 0\]MATLAB code is available to solve this linear program where A, E, e, F, and f are givens and we are trying to solve for x and y. The code also includes variables p and q, which we don’t go into here except for the first value of the p vector, which is the game value.

%givens

A=[0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

0,0,0,0,0,2,1,0,0,2,1,0,0;

0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,1;

0,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,0,0,0,2,0;

0,0,0,0,0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,-1,0;

0,-2,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,1,0,0;

0,0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1;

0,0,0,-2,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,0;

0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,-1,0;

0,-2,1,0,0,-2,1,0,0,0,0,0,0;

0,0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,0;

0,0,0,-2,0,0,0,-2,0,0,0,0,0;

0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,-1,0,0,0,0,0]/6.;

F=[1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1];

f=[1;0;0;0;0;0;0];

E=[1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

0,0,-1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0;

0,0,0,0,0,0,-1,1,1,0,0,0,0;

-1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,0;

0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,-1,1,1];

e=[1;0;0;0;0;0;0];

%get dimensions

dim_E = size(E)

dim_F = size(F)

%extend to cover both y and p

e_new = [zeros(dim_F(2),1);e]

%constraint changes for 2 variables

H1=[-F,zeros(dim_F(1),dim_E(1))]

H2=[A,-E']

H3=zeros(dim_E(2),1)

%bounds for both

lb = [zeros(dim_F(2), 1);-inf*ones(dim_E(1),1)]

ub = [ones(dim_F(2), 1);inf*ones(dim_E(1),1)]

%solve lp problem

[yp,fval,exitflag,output,lambda]=linprog(e_new,H2,H3,H1,-f,lb,ub);

%get solutions {x, y, p, q}

x = lambda.ineqlin

y = yp(1 : dim_F(2))

p = yp(dim_F(2)+1 : dim_F(2)+dim_E(1))

q = lambda.eqlin

The output is:

Optimal solution found.

x =

1.0000

1.0000

0

0

0

0

1.0000

0.6667

0.3333

0.3333

0.6667

0

0.6667

y =

1.0000

1.0000

0

1.0000

0

0.3333

0.6667

-0.0000

1.0000

-0.0000

1.0000

0.3333

0.6667

p =

-0.0556

0.3889

0.1111

-0.1111

-0.2222

-0.3333

-0.1667

q =

0.1111

-0.1111

-0.3889

0.2222

-0.1111

0.3333

0.1667

The \(x\) and \(y\) values are a Nash equilibrium strategy solution for each player (one of many equilibrium solutions), whereby the values after the first in the vector describe the betting strategy for each of the actions for each player as shown in the vectors above. The first \(p\) value shows the value of the game as we had calculated before in the analytical section: -0.0556.

Iterative Algorithms

Now we have shown a way to solve games more efficiently based on the structure/ordering of the decision nodes.

Using behavioral strategies significantly reduces the size of the game and solving is much more efficient by using the structure/ordering of the decision nodes. This can be expresessed in tree form and leads to algorithms that can use self-play to iterate through the game tree.

Specifically CFR (Counterfactual Regret Minimization) has become the foundation of imperfect information game solving algorithms. We will go into detail on this in Section 4.1.

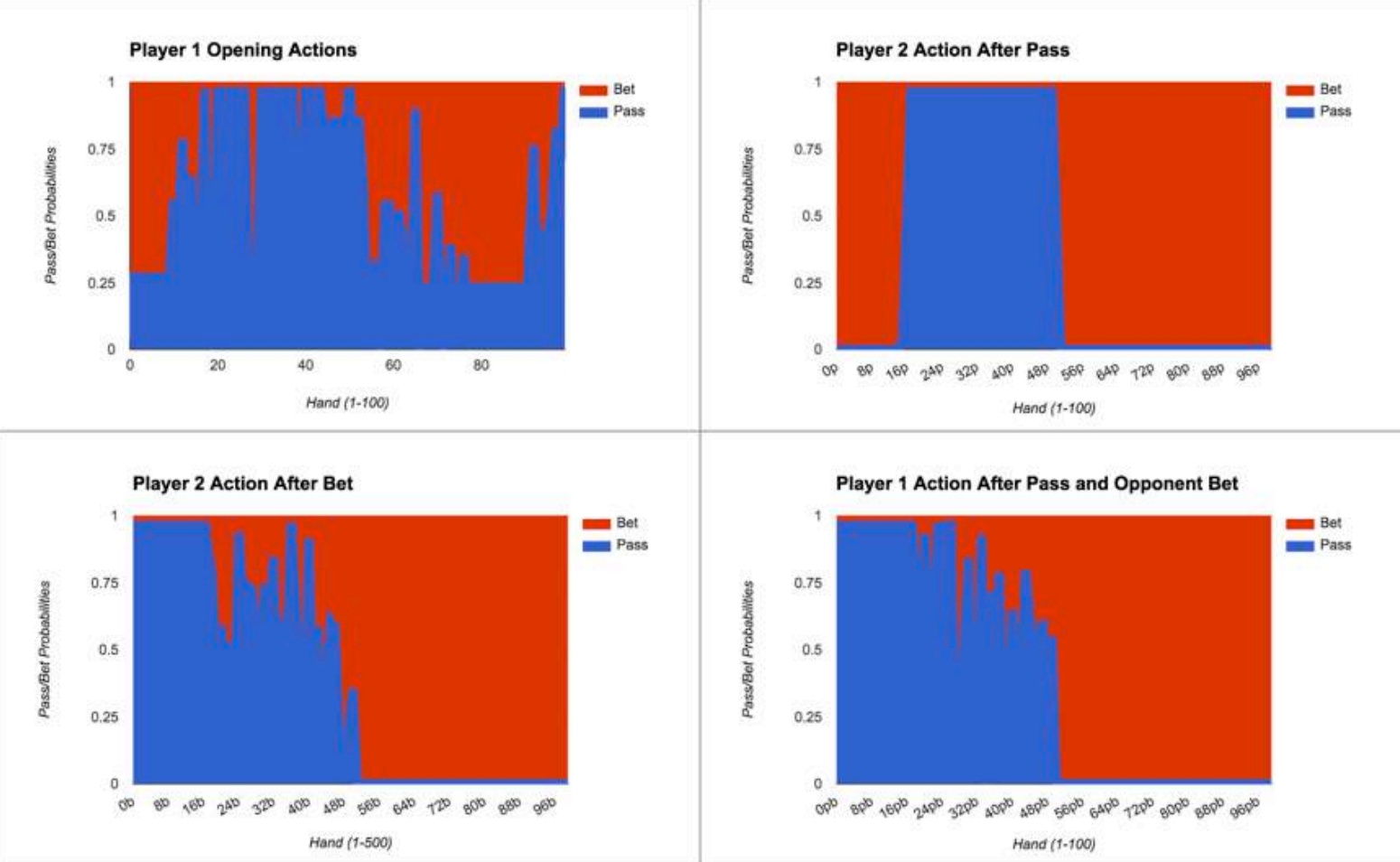

We can see a visualization of the optimal strategy that was solved in 100-card Kuhn Poker using the CFR algorithm. The strategy for the following charts was computed using 10^9 iterations of External Sampling CFR (see Section 4.1). The Player 1 Opening Actions represent the general strategy of mostly betting good and bad hands, while passing on medium-strength hands, and also passing on the very best hands. The Player 2 Action After Pass chart uses the same logic, although with no passing on the best hands or worst hands because this is the final action, so a pass would simply end the hand, which would generally mean no chance of winning with poor hands and no chance of earning value with good hands.

The Player 2 Action After Bet and Player 1 Action After Pass and Opponent Bet are quite similar as both represent the situation of facing a bet with no additional money behind (i.e., no bluffs are possible), so the only decision is to call the bet or fold, so naturally we call with our better hands.

The horizontal axis represents the hands in order given the situation and the bars above each represent the probability of betting, with fully blue meaning always Pass, fully red meaning always Bet, and some of each meaning the mixture of the two.

We see that this is similar to what we’d expect from learning the 3-card game, but with some additional complexity.

The bottom two graphs are not very informative because they only show that when facing the final bet, you should call with better hands and fold worse hands. However, from the Player 1 Opening Actions graph (and with similar principles applied to the Player 2 Action After Pass graph), the idea is that the good hands that we bet are value-bets meant to get called by worse hands. The passing with the very best hands is called slow-playing and the betting with the worst hands is called bluffing. Both deceptive moves give the strategy a balance and the bluff gives a chance to win with hands that otherwise would have no chance of winning. Not betting with middling hands is effective because betting would generally cause worse hands to fold and keep better hands in. The principles are the same as in the 3 card version, but more cards allows for a sharper understanding of the general strategy.