AIPT Section 4.3: CFR – Agent Evaluation

CFR - Agent Evaluation

Poker results are generally measured in big blinds per 100 hands won. In the research community, the standard measure is milli-big-blinds per hand (or per game), or mbb/g, where one milli-big-blind is 1/1000 of one big blind. This is also used as a measure of exploitability, the expected loss per game against a worst-case opponent. A player who folds every hand will lose 750 mbb/g on average in a heads up match (1000 mbb/g as big blind and 500 as small blind).

Evaluating Poker Agents

There are three main ways to evaluate poker agents – against a best response opponent, against other poker agents, and against human opponents. Evaluation can be difficult due to the inherent variance in poker, but this can be minimized by playing a very large number of hands and also by playing in a “duplicate” format, where, for example, two agents would play a set of hands and then clear their memories and play the same hands with the cards reversed (only possible when humans are not involved). Further, an agent that performs well in one evaluation metric is not guaranteed to perform well in others.

Best Response

We can find the best response to a poker agent’s strategy analytically by having its opponent always choose the action that maximizes expected value against the agent’s strategy in all game states, given the agent’s strategy. We can then compute the e in the e-Nash equilibria as a measure of exploitability that gives the lower bound on the exploitability of the agent.

The purpose of calculating a best response is to choose actions to maximize our expected value given an opponent’s entire strategy. The expectimax algorithm involves a simple recursive tree walk where the probability of the opponent’s hand is passed forward and the expected value for our states (I – information sets) returned, involving just one pass over the entire game tree.

Best response usually requires a full tree traversal, but Johansen et al. showed a general technique that can avoid this in their paper “Accelerating Best Response Calculation in Large Extensive Trees”, since full tree traversal is often infeasible in very large games.

Best response has advantages over comparing strategies by competing them against each other since it is a more theoretical measure and because problems can arise when doing agent vs. agent evaluations, like intransitivities (e.g. Agent A beats Agent B and Agent B beats Agent C but Agent C beats Agent A) and variance.

The standard best response method involved “examining each state once to compute the value of every outcome, followed by a pass over the strategy space to determine the optimal counter-strategy”.

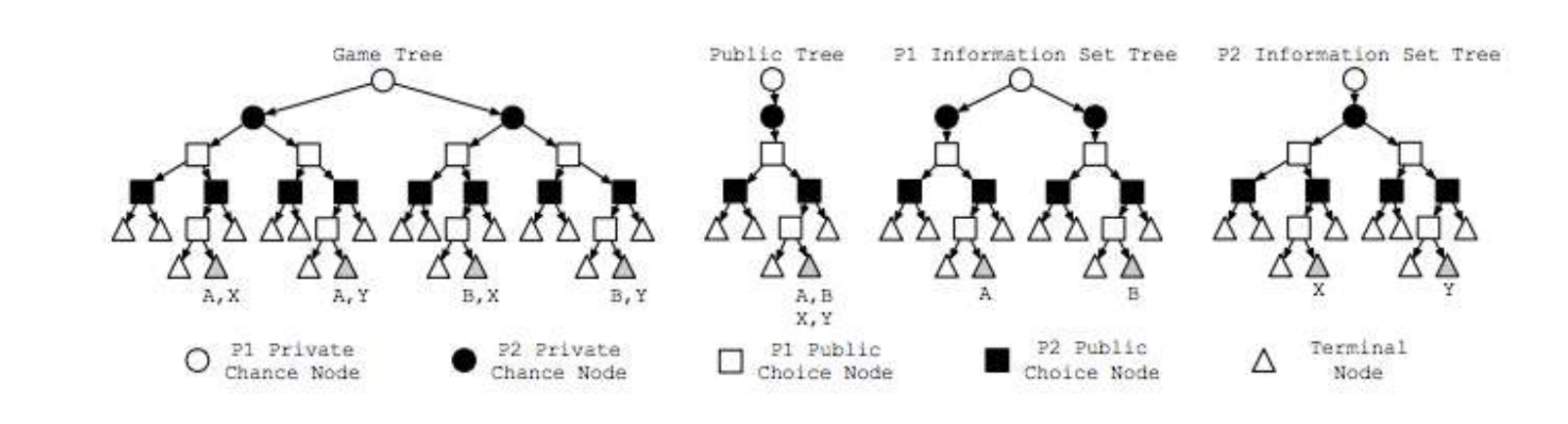

This figure shows different trees representing Kuhn (1-card) poker. The left tree, titled Game Tree, shows the exact state of the game. The squares are public nodes since bets are made publicly, while the circles are private nodes since player cards are private only to them. In the two rightmost trees (P1 and P2 Information Set Trees), the opponent chance nodes have only one child each since their chance information is unknown to the other player.

Instead of walking the full game tree or even the information set trees, it was shown that we can improve the algorithm by walking only the public tree and visiting each state only once. When we reach a terminal node such as “A,B,X,Y”, this means that player 1 could be in nodes A or B as viewed by player 2 and that player 2 could be in nodes X or Y as viewed by player 1. The algorithm calls for passing forward a vector of reach probabilities of the opponent and chance and recursing back, while choosing the highest valued actions for the iteration player’s perspective and returning the sum of child values for the opponent player, and then at the root, the returned value is the best response to the opponent’s strategy.

Michael Johanson’s paper describes techniques for accelerating best response calculations using the structure of information and utilities to avoid a full game tree traversal, allowing the algorithm to compute the worst case performance of non-trivial strategies in large games.

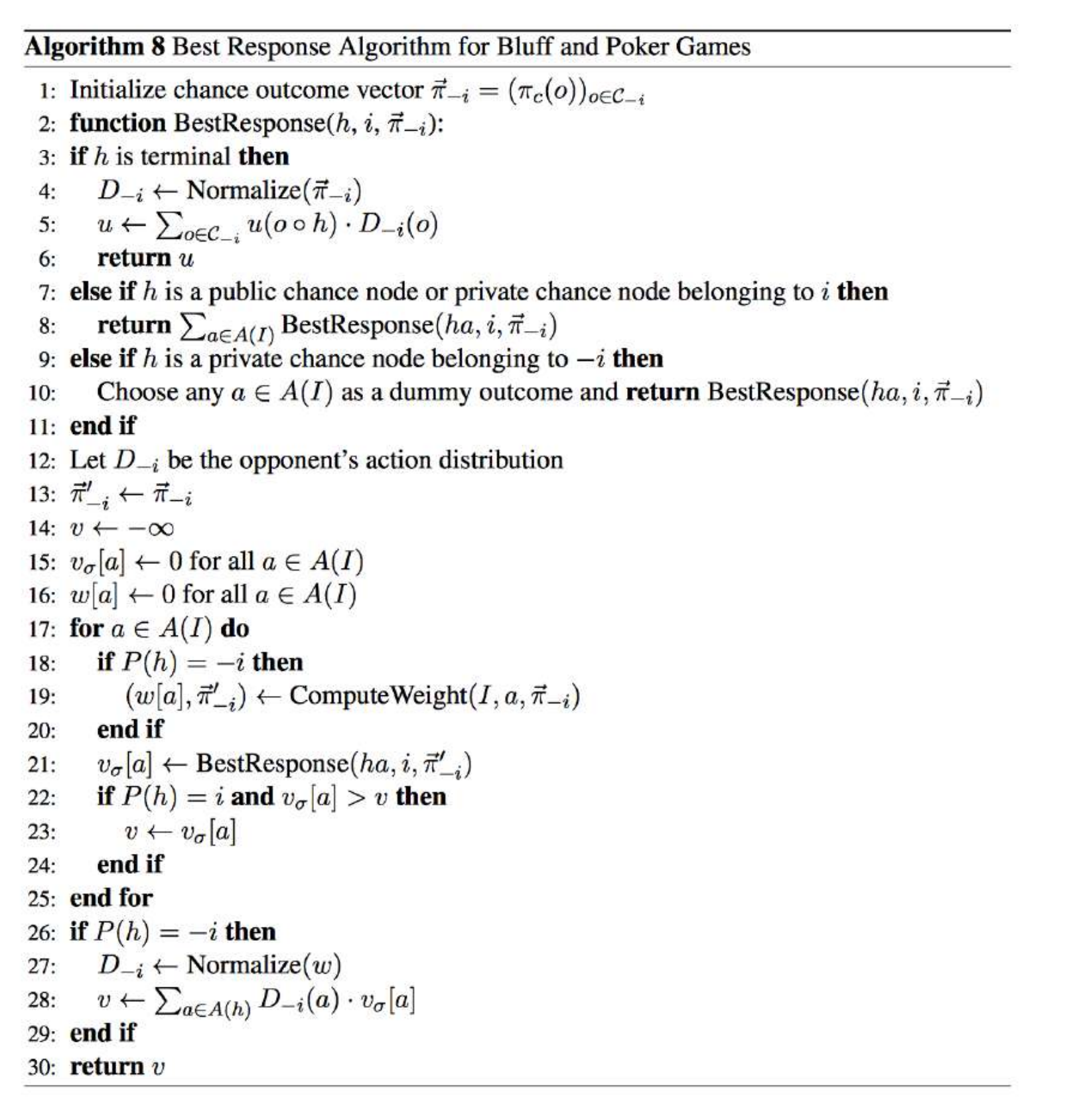

The best response algorithm in the below figure takes as inputs the history of the actions, the current player (the algorithm must be run for each player), and a distribution of the opponent reach probabilities (line 2). An additional D variable is set on line 12 to define the opponent’s action distribution. Then for each action possible, if the node does not belong to the current player, then we iterate over each opponent possible cards, find the probability of the player playing those cards, and update the reach probability accordingly. A new variable w[a] is also introduced on line 19 to sum the probabilities over all cards that are taking a certain action. Line 21 recurses over the best response function to find the value of taking each action from that node, and then on line 22-23, if that action value is better than the previous value (which is defaulted at negative infinity), then it is assigned as the value for that node.

On lines 26-28, if the node is not the current player, then the w values are normalized to define the opponent’s action distribution and the node is assigned a value according to the action distribution and the node action values (i.e. this node’s value is assigned with the normal weights, as opposed to the current player’s node value that is assigned according to the best response method).

Finally, on lines 3-6, at terminal points, the opponent distribution is normalized, values are assigned from the perspective of the iteration player, and the expected value payoff is computed as a multiplication between the payoff and the normalized opponent distribution

Here’s how the algorithm works in practice in conjunction with CFR:

- Pause CFR intermittently

- Call the best response function (BRF) for each player separately (this player is called the iterating or traversing player)

- Iterate over all cards and sum all to get overall best respones for each iterating player

- Pass to BRF:

- Player card of iterating player

- Root starting history

- Which player is iterating player

- Vector of uniform reach probabilities of opponent hand possibilities

- Example in 5 card Kuhn poker: Player card = 3. Opponent vector = [0.25, 0.25, 0.25, 0, 0.25]

- If at a terminal node, normalize the vector of the opponent reach probabilities and for each possible opponent hand, add the probability of that hand * the payoff from the iterating player’s perspective. Then return the expected payoff after going through all possible hands.

- If not at a terminal node, create the following:

- D = [0, 0] to track the opponent’s action distribution

- V = -inf for the value of the node

- New opponent reach probabiltiies that are initialized as a copy of the previous ones

- Util = [0, 0] to track the utility of each action

- W = [0, 0]

- Iterate over the actions:

- If the acting player is not the iterating player:

-

- Iterate over all hands of this player

-

- Get the strategy of the actin gplayer for each hand based on what CFR has found up to now

-

- Update the acting player reach probabilities multiplied by the strategy

-

- W[action] += each of the new reach probabiltiies for this action

- Set the utility of this action to a recursive BRF call with the new history and new opponent reach (only changed if the acting player is not the iterating player)

- If the acting player is the iterating player and the utility of this action is higher than the current V, then set V = util[this action] since the iterating player will play the best pure strategy

- If the acting player is not the iterating player:

- D = the normalization of W over each action (i.e., D[0] = W[0]/(W[0] + W[1]))

- V = D[0] * util[0] * D[1] * util[1]

- Return V

Here is an implementation of the best response function in Python for Kuhn Poker:

import numpy as np

def brf(self, player_card, history, player_iteration, opp_reach):

plays = len(history)

acting_player = plays % 3

expected_payoff = 0

if plays >= 3: #can be terminal

opponent_dist = np.zeros(len(opp_reach))

opponent_dist_total = 0

#print('opp reach', opp_reach)

if history[-1] == 'f' or history[-1] == 'c' or (history[-1] == history[-2] == 'k'):

for i in range(len(opp_reach)):

opponent_dist_total += opp_reach[i] #compute sum of dist. for normalizing

for i in range(len(opp_reach)):

opponent_dist[i] = opp_reach[i] / opponent_dist_total

payoff = 0

is_player_card_higher = player_card > i

if history[-1] == 'f': #bet fold

if acting_player == player_iteration:

payoff = 1

else:

payoff = -1

elif history[-1] == 'c': #bet call

if is_player_card_higher:

payoff = 2

else:

payoff = -2

elif (history[-1] == history[-2] == 'k'): #check check

if is_player_card_higher:

payoff = 1

else:

payoff = -1

expected_payoff += opponent_dist[i] * payoff

return expected_payoff

d = np.zeros(2) #opponent action distribution

d = [0, 0]

new_opp_reach = np.zeros(len(opp_reach))

for i in range(len(opp_reach)):

new_opp_reach[i] = opp_reach[i]

v = -100000

util = np.zeros(2)

util = [0, 0]

w = np.zeros(2)

w = [0, 0]

#infoset = history

for a in range(2):

if acting_player != player_iteration:

for i in range(len(opp_reach)):

infoset = str(i) + history

if infoset not in self.nodes:

self.nodes[infoset] = Node(2)

strategy = self.nodes[infoset].get_average_strategy()#get_strategy_br()

new_opp_reach[i] = opp_reach[i] * strategy[a] #update reach prob

w[a] += new_opp_reach[i] #sum weights over all poss. of new reach

if a == 0:

if len(history) != 0:

if history[-1] == 'b':

next_history = history + 'f'

elif history[-1] == 'k':

next_history = history + 'k'

else:

next_history = history + 'k'

elif a == 1:

if len(history) != 0:

if history[-1] == 'b':

next_history = history + 'c'

elif history[-1] == 'k':

next_history = history + 'b'

else:

next_history = history + 'b'

#print('w', w)

#print('history', history)

#print('next history', next_history)

util[a] = self.brf(player_card, next_history, player_iteration, new_opp_reach)

#print('util a', util[a])

if (acting_player == player_iteration and util[a] > v):

v = util[a] #this action better than previously best action

if acting_player != player_iteration:

#D_(-i) = Normalize(w) , d is action distribution that = normalized w

d[0] = w[0] / (w[0] + w[1])

d[1] = w[1] / (w[0] + w[1])

v = d[0] * util[0] + d[1] * util[1]

return v

Agent vs. Agent

Agent against agent is a common way to test the abilities of poker programs. This is an empirical method for researchers to evaluate agents with different characteristics, such as different abstractions. If a game theory optimal agent exists for a game then another agent could play against the GTO agent as a measure of quality.

Researchers from around the world competed annually at the Annual Computer Poker Competition that began in 2006 and is now part of the Poker Workshop at the annual AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. It has competitions in limit, no-limit, and later 3 player Kuhn poker (most recently only no limit competitions were played). This uses duplicate matches and two winner determination methods – instant run-off, which eliminates the worst agent in each round and bankroll, which gives the win to the agent with the highest bankroll in that event. This means that there are different incentives for agents that play a more defensive vs. more aggressive strategy.

Human Opponents

The main issue with playing against human opponents is that win-rates can take approximately one million hands to converge. The 2015 Man vs. Machine competition involved 80,000 hands total against four opponents, which led to disputes over statistical significance of the results.

Despite the difficulty of achieving very large hand samples against human opponents, there is still value in these test games, as human experts are capable of quickly analyzing a strategy and the playing statistics of that strategy, so a computer program can be sanity checked and evaluated for unique tendencies by such human experts. Computer programs could also be made available on the Internet to play against many opponents to obtain significant levels of data. In practice, most of the breakthrough agents have only been released to play against select top players since this is considered more significant than playing against random players and perhaps to keep the agents’ strategies more private.